ESTRAGON: I'm unhappy. VLADIMIR: Not really! Since when? ESTRAGON: I'd forgotten. VLADIMIR: Extraordinary the tricks that memory plays!

If, as some people claim, the characters in Waiting for Godot are to be analogous to voices in our heads, then this conversation is one which is oft to occur over and over again. Occasionally, one might pinpoint misery to an accidental event, a lapse of concentration of our guardian angels above. Yet, as edginess gets a new name, “existential dread,” I am led to question, in logic which runs itself in circles, the imperfect nature of our existence, or more crudely, the meaning of life.

I feel this phase to be fundamentally inevitable, a rite of passage as one grows up, a phase which returns in the haunting images of “mid-life crisis” and the fear of death. As all roads lead to Rome, any examination into life seems to lead back to this question, like an unproved axiom upon which every other theorem is built upon. One learns, however, to find value in the theorems which seem to lack proper foundation, and yet are practically useful nonetheless. The unexamined life is not worth living, but if one were to spend their entire lives examining that which cannot be answered, could one really call it a life at all?

I do not aim to provide anywhere near a comprehensive discussion on postmodernism, merely bits and pieces which have helped me, chosen more by pure chance of me stumbling upon them rather than intentionally.

what we have so far

The answer, philosophy and literature finds, is the idea of the absurd, which has made its way to the frontlines of bookstores in the form of Camus and Kafka, now placed under “bestseller” or “recommends.” One must not discount Dostoyevsky, and existentialist thought prompted by Viktor Frankl and his life-altering book The Search for Meaning, in which he suggests that the purpose of life lies not in its overall picture, but rather in the small, incremental moments in which must create meaning to live to the next. i.e., baby steps.

The absurd, however, holds that life itself must be meaningless, not in the nature of its futility but instead that the very question, “What is the meaning of life?” is meaningless in itself. It would be akin to asking the meaning of happiness. Only after one has accepted the inherent absurdity of life as a situation, can one fully appreciate and live. Perhaps it is due to the masochistic obsession with the problem, or merely a pretentious refusal to conform to normality, but it is to my great disadvantage that I have never read a Camus book, only summaries and video essays. Thus, this short essay could be taken as a “before” image of my mind, before (hopefully), I pick up a copy of The Myth of Sisyphus. My understanding of the absurd must thus be taken to be incomplete.

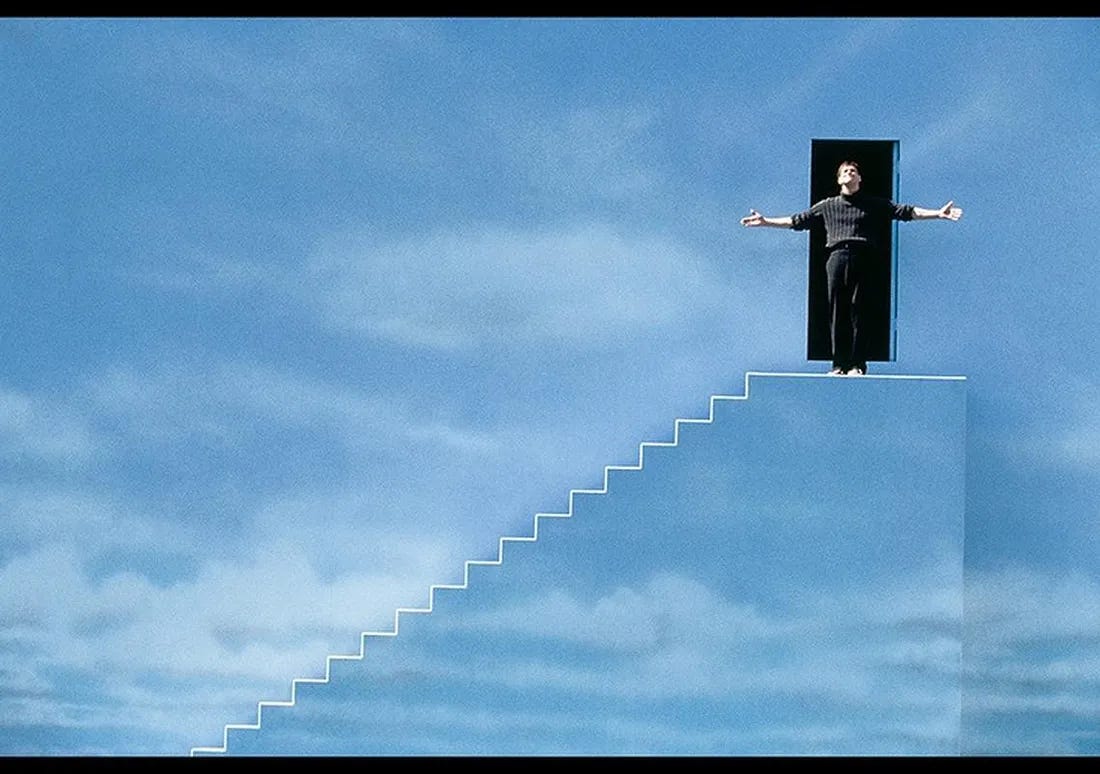

The sentiment of absurdism is echoed in the postmodernism movement, which is characterised by the skeptical, the subjective, and an attitude of total doubt about everything which has come before. Like Truman who realises he’s in a simulation. Such a movement was prompted, in part by the general decline of religiousness in Europe, as exemplified by Nietzsche “God is dead,” and catalysed by the horrors of both world wars which prompted artists to question the brutality of man, and in all likelihood fuelled by the artists’ trauma itself. It is easy to see postmodernism as the norm, given that its effects have far-reaching consequences on our present-day idea of normality, but such a movement was significant insofar as it served to question the blind faith of religion, power structures, and beliefs which otherwise dictated life with clockwork precision. Of course, a loss of faith is accompanied by the question, now what? Now that little is left, one has to contest meaninglessness. We are Truman, but instead of a new, concrete, real world in which we emerge, instead we find desolate emptiness, space stretching infinitely into the horizon. There is no foundation, no anchor to reality, besides our presence.

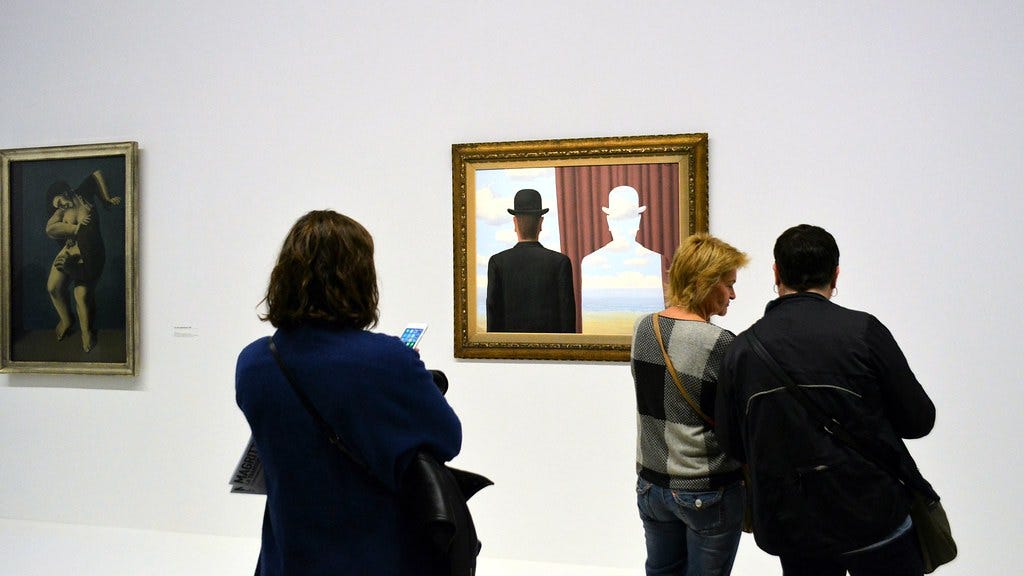

It is thus from this that we have my favourite art movement, surrealism. I am no art expert, but insofar as I understand, surrealism was prompted by very much the same ideas which led to postmodernism, and added onto previous movements (neo-impressionism and modernism). It was also influenced largely by Freud’s examination into the unconscious, and the dream-like worlds created by Surrealist artists mirror the unconscious mind. It is often characterised by physically impossible scenes, depicting everyday objects (or otherwise) in totally unrealistic, intentionally dream-like dimensions. To me, it offers an opportunity away from reality, providing a form of escapism whilst somehow mirroring reality in curious manners, thus serving as a lens with which we examine ourselves from new perspectives.

From the other side of the same page, we have Zdzisław Beksiński, who provided much inspiration for heavy metal album covers, and expressed much of his WW2 trauma through his art, often depicting dystopian scenes of gore and war imagery. Much of his work might be unappealing to more sensitive viewers, but I heavily recommend exploring “the nightmare artist”. When questioned about the meaning behind the heavy symbolism in his work, he simply answered, 'meaning is meaningless to me,’ echoing the narrative of the postmodern movement.

Finally, we have Samuel Beckett, the Nobel Prize-winning writer from whom we have the gems of all postmodernist literature, at the forefront of which (i consider) to be the play Waiting for Godot. This play itself deserves a post of its own, but as an extension of the discussion here. Waiting for Godot is a play where, well, two individuals wait for.. Godot. And (spoiler alert) he never comes, but they wait anyways, like Sisyphus and his boulder which has come to represent everything but a huge rock up a mountain, and very much our own lives (washing the dishes everyday is surely akin to a rolling a boulder up a mountain).

ESTRAGON: What do we do now? VLADIMIR: I don't know. ESTRAGON: Let's go. VLADIMIR: We can't. ESTRAGON: Why not? VLADIMIR: We're waiting for Godot.

To me, the play is the most accurate representation of absurdism, with its complex series of metaphors and literary devices which offer to the reader a plethora of material to analyse, dissect, and assign meaning to individual parts. But much like the nature of life itself, it also provides a more superficial, direct narrative - the absurd. The play has, effectively, no plot nor characterisations, often descends into pure nonsense (qua qua qua), and is memorable only due to its sheer absurdity. It is, perhaps, not meant to be examined, but meant to merely exist, as all plays do, for the pure enjoyment of its audience in any form they deem fit. If enjoyment is derived from analysis, then by all means. But it is also a space of silence, from one’s thoughts, where nothing happens, precisely so nothing else can happen. By the end of the play, the audience has come to accept, like Vladimir and Estragon, that they are merely waiting for Godot.

(it can be said that the first piece of work which prompted me on this journey is the short story Symbols and Signs by Vladimir Nabokov, available through The New Yorker)

what now?

Undoubtedly, like every generation before us, we are a troubled one. Deaths of despair continue to dominate statistics in the richest developed country in the world, wars rage on after centuries of unlearnt lessons, politics continues to be dominated by power structures where the pyramid is built on wealth. We are teetering on a climate change crisis, facing a mental health pandemic where hopelessness becomes commonplace. Yes, we are a strawberry generation of weak, meek and easily broken individuals, but that does not negate the fact that there are still people breaking.

It is easy, too easy, to look at the front page of the news, scroll a few posts of romanticised lives, and procure cheap forms of escapism in the form of Netflix shows stolen by revenge bedtime procrastination. It is easy to look upon it all and fall into the deep pit of dread and anxiety. But as Nietzche said,

“He who fights with monsters should look to it that he himself does not become a monster. And if you gaze long into an abyss, the abyss also gazes into you.”

It warns of the dangers of doing evil, but I also find it fitting as an aphorism cautioning obsession, especially obsession over meaning and purpose. There is no justice in demarcating Netflix as escapism, nor is there justice in labelling philosophy and art as the most important endeavours known to man. As with all things, all must be done in moderation. But for the occasional midnight thought, there are a few solutions when we ask, “but what is it all for?” I seem to be waiting for something, an epiphany triggered by the wisdom of age, but conversations with old people are enough to show me that, even by then, most of us haven’t figured it out yet.

So it seems that either we create our own meaning, by means of logotherapy and existentialism, or we don’t, and grapple with the absurd. Regardless, if one is to accept Kafkaesque thinking, one must accept the image of Gregor Samsa, and the absurd striving towards life. Because all living things must grow.

There are facts with which we cannot contend, which all the art and literature here must accept as first principles. We are alive, painfully or otherwise, and the world exists as it is, evil or otherwise. One can consult the Tarot deck (to which I have fallen victim), or write a dissertation carefully citing centuries of accumulated thought. Ultimately, meaning is not a universal question, but a subjective, personal accumulation of beliefs, friends, commitments and identity. It is, indubitably, critical to be alive consciously, to strive and to embody passion in one’s life. The question is a necessary one, though its open-ended nature is not a invitation into despair. I must not obsess with duration, for the same question which asks “until when?” is the organ which proclaims time to be subjective.

In conclusion (if one can conclude the mess that is this post), futility is defined only by what is useful, and what is useful is very different for a farmer and a billionaire. But ultimately, I have a long way ahead, and next to nothing figured out about the questions that billions have raised before me. Often, I sit around and ask the ceiling before I sleep, “what are we all waiting for?”

It is all silent, but I wish it would say, waiting for Godot.

Thank you for reading my first substack post!! As a clueless high school student, I hope I can catalogue my growing pains through writing, and hopefully you liked this piece! If you like discussions like this, do subscribe!

Attributions:

“Waiting for Godot” from SilverTD through Flickr

“The Truman Show” from Kyle Nordwall through Medium

"Looking at Magritte IV" by C. B. Campbell is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

“The Metamorphosis” - Metraproceso, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons